I recently happened upon a 14 volume set of Little Journeys at a local second-hand bookshop. I was practically giddy with excitement to find these, especially the volume that includes Rossetti and Elizabeth Siddal. I’ve scanned the book and transcribed the text. Other volumes include Christina Rossetti, William Morris, and John Ruskin. I plan on transcribing these as well.

Little Journeys was a series written by Elbert Hubbard. I was not familiar with him prior to purchasing his works, but I was interested to see on his wikipedia entry that he founded an Arts and Crafts community in Aurora, New York and that his printing press was inspired by William Morris’s Kelmscott Press.

I know that reading a large chunk of text online is a different experience than reading a book. It can seem tedious. But I felt it would be an important addition to this website to be able to offer the transcribed text for anyone who would care to read it. And, as always, I look forward to reading your comments should you choose to post one!

Scans of the book, transcription below the images:

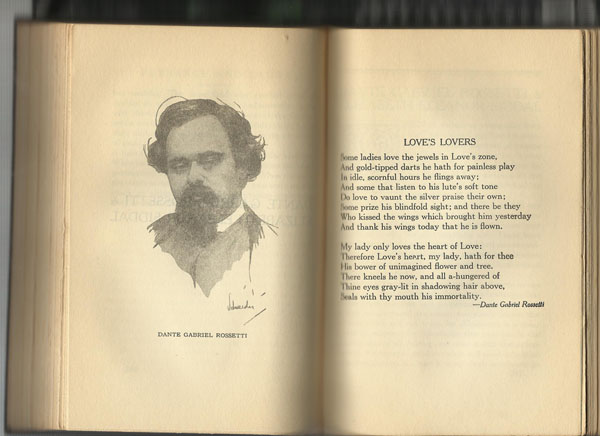

DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI AND ELIZABETH ELEANOR SIDDAL

LOVE’S LOVERS

Some ladies love the jewels in Love’s zone,

And gold-tipped darts he hath for painless play

In idle, scornful hours he flings away;

And some that listen to his lute’s soft tone

Do love to vaunt the silver praise their own;

Some prize his blindfold sight; and there be they

Who kissed the wings which brought him yesterday

And thank his wings today that he is flown.

My lady only loves the heart of Love:

Therefore Love’s heart, my lady, hath for thee

His bower of unimagined flower and tree.

There kneels he now, and all a-hungered of

Thine eyes gray-lit in shadowing hair above,

Seals with thy mouth his immortality.

–Dante Gabriel Rossetti

When an ambitious young man from the “provinces” signified his intention

to Colonel Ingersoll of coming to Peoria and earning an honest

livelihood, he was encouraged by the Bishop of Agnosticism with the

assurance that he would find no competition.

Personally, speaking for my single self, I should say that no man is in

so dangerous a position as he who has no competition in well-doing.

Competition is not only the life of trade, but of everything else. There

have been times when I have thought that I had no competition in

truth-telling, and then to prevent complacency I entered into

competition with myself and endeavored to outdo my record.

The natural concentration of business concerns in one line, in one

locality, suggests the many advantages that accrue from attrition and

propinquity. Everybody is stirred to increased endeavor; everybody knows

the scheme which will not work, for elimination is a great factor in

success; the knowledge that one has is the acquirement of all. Strong

men must match themselves against strong men: good wrestlers will need

only good wrestlers. And so in a match of wit rivals outclassed go

unnoticed, and there is always an effort to go the adversary one better.

Our socialist comrades tell us that “emulation” is the better word, and

that “competition” will have to go. The fact is that the thing itself

will ever remain the same–what you call it matters little. We have,

however, shifted the battle from the purely physical to the mental and

psychic plane. But it is competition still, and the reason competition

will remain is because it is beautiful, beneficent and right. It is the

desire to excel. Lovers are always in competition with each other to see

who can love most.

The best results are obtained where competition is the most free and

most severe–read history. The orator speaks and the man who rises to

reply had better have something to say. If your studio is next door to

that of a great painter, you had better get you to your easel, and

quickly, too.

The alternating current gives power: only an obstructed current gives

either heat or light; all good things require difficulty. The Mutual

Admiration Society is largely given up to criticism.

Wit is progressive. Cheap jokes go with cheap people; but when you are

with those of subtle insight, who make close mental distinctions, you

should muzzle your mood, if perchance you are a bumpkin.

Conversation with good people is progressive, and progressive inversely,

usually, where only one sex is present. Excellent people feel the

necessity of saying something better than has been said, otherwise

silence is more becoming. He who launches a commonplace where high

thoughts prevail is quickly labeled as one who is with the yesterdays

that lighted fools adown their way to dusty death.

Genius has always come in groups, because groups produce the friction

that generates light. Competition with fools is not bad–fools teach the

imbecility of repeating their performances. A man learns from this one,

and that; he lops off absurdity, strengthens here and bolsters there,

until in his soul there grows up an ideal, which he materializes in

stone or bronze, on canvas, by spoken word, or with the twenty-odd

little symbols of Cadmus.

Greece had her group when the wit of Aristophanes sought to overtop the

stately lines of AEschylus; Praxiteles outdid Ictinus; and wayside words

uttered by Socrates were to outlast them all.

Rome had her group when all the arts sought to rival the silver speech

of Cicero. One art never flourishes alone–they go together, each man

doing the thing he can do best. All the arts are really one, and this

one art is simply Expression–the expression of Mind speaking through

its highest instrument, Man.

Happy is the child who is born into a family where there is a

competition of ideas, and where the recurring theme is truth. This

problem of education is not so very much of a problem after all.

Educated people have educated children, and the best recipe for

educating your child is this: Educate yourself.

—–

The Rossettis were educated people: each was educated by all and all by

each.

Individuality was never ironed out, for no two were alike, and between

them all were constantly little skirmishes of wit, and any one who

tacked a thesis on the door had to fight for it. Luther Burbank rightly

says that children should not be taught religious dogma. The souls of

the Rossettis were not water-logged by religious belief formulated by

men with less insight and faith than they.

In this way they were free. And so we find the father and the mother,

blessed by exile in the cause of liberty, living hard, plain lives, in

clean yet dingy poverty, with never an endeavor to “shine” in society or

to pass for anything different than what they were, and never in debt a

penny to the haberdasher, the dressmaker, the milliner or the grocer.

When they had no money to buy a thing they wanted, they went without it.

Just the religion of paying your way and being kind would be a pretty

good sort of religion–don’t you think so?

So now, behold this little Republic of Letters, father and mother and

four children: Maria, Christina, Dante Gabriel and William Michael.

The father was a poet, musician and teacher. The mother was a

housekeeper, adviser and critic, and supplied the necessary ballast of

commonsense, without which the domestic dory would surely have turned

turtle.

Once we hear this good mother saying, “I always had a passion for

intellect, and my desire was that my husband and my children might be

distinguished for intellect; but now I wish they had a little less

intellect, so as to allow for a little more commonsense.”

This not only proves that this mother of four very extraordinary and

superior children had wit, but it also seems to show that even intellect

has to be bought with a price.

I have read about all that has been written concerning Rossetti and the

Preraphaelite Brotherhood by those with right and license to speak. And

among all those who have set themselves down and dipped pen in ink, no

one that I have found has emphasized the very patent truth that it was a

woman who evolved the “Preraphaelite Idea,” and first exemplified it in

her life and housekeeping.

It was Frances Polidora Rossetti who supplied Emerson that fine phrase,

“Plain living and high thinking.” Of course, it might have been original

also with Emerson, but probably it reached him via the Ruskin and

Carlyle route.

Emerson also said, “A few plain rules suffice,” but Mrs. Rossetti ten

years before put it this way, “A few plain things suffice.” She had a

horror of debt which her husband did not fully share. She preferred

cleanly poverty and honest sparsity to luxury on credit. In her

household she had her way. Possibly it was making a virtue of

necessity, but she did it so sincerely and gracefully that prenatally

her children accepted the simplicity of their Preraphaelite home as its

chief charm.

Without the Rossettis the Preraphaelite Brotherhood would never have

existed. It will be remembered that the first protest of the Brotherhood

was directed against “Wilton carpets, gaudy hangings, and ornate,

strange and peculiar furniture.”

Christina Rossetti once told William Morris that when she was but seven

years old her mother and she congratulated themselves on the fact that

all the furniture they had was built on straight and simple lines, that

it might be easily cleaned with a damp cloth. They had no carpets, but

they possessed one fine rug in the “other room” which was daily brought

out to air and admire. The floors were finished in hard oil, and on the

walls were simply the few pictures that they themselves produced, and

the mother usually insisted on having only “one picture in a room at a

time, so as to have time to study it.”

So here we get the very quintessence of the entire philosophy of William

Morris: a philosophy which, it has well been said, has tinted the entire

housekeeping world.

In his magazine, called, somewhat ironically, “Good Words,” Dickens

ridiculed, reviled and berated the Preraphaelite Idea. Of course,

Dickens didn’t understand what the Rossettis were trying to express.

He called it pagan, anti-Christian, and the glorification of pauperism.

Dickens was born in a debtor’s prison–constructively–and he leaped

from squalor into fussy opulence. He wrote for the rabble, and he who

writes for the rabble has a ticket to Limbus one way. The Rossettis made

their appeal to the Elect Few. Dickens was sired by Wilkins Micawber and

dammed by Mrs. Nickleby. He wallowed in the cheap and tawdry, and the

gospel of sterling simplicity was absolutely outside his orbit. Dickens

knew no more about art than did the prosperous beefeater, who, being

partial to the hard sound of the letter, asked Rossetti for a copy of

“The Gurm,” and thus supplied the Preraphaelites a title they

thenceforth gleefully used.

But the abuse of Dickens had its advantages–it called the attention of

Ruskin to the little group. Ruskin came, he saw, and was conquered. He

sent forth such a ringing defense of the truths for which they stood

that the thinking people of London stopped and listened. And this caused

Holman Hunt to say, “Alas! I fear me we are getting respectable.”

Ruskin’s unstinted praise of this little band of artists was so great

that he convinced even his wife of the truth of his view; and as we

know, she fell in love with Millais, “the prize-taking cub,” and they

were married and lived happily ever after.

Ruskin and Morris were both born into rich families, where every luxury

that wealth could buy was provided. Having much, they knew the

worthlessness of things: they realized what Walter Pater has called “the

poverty of riches.” Dickens had only taken an imaginary correspondence

course in luxury, and so Wilton carpets and marble mantels gave him a

peace which religion could not lend. A Wilton carpet was to him a

Christian prayer-rug.

The joy of discovery was Ruskin’s: he found the Rossettis and gave them

to the world. Ruskin was a professor at Oxford, and in his classes were

two inseparables, William Morris and Burne-Jones. They became infected

with the simplicity virus; and when Burne-Jones went up to London, which

is down from Oxford, he sought out the man who had painted “The Girlhood

of the Virgin,” the picture Charles Dickens had advertised by declaring

it to be “blasphemously idolatrous.”

Burne-Jones was so delighted with Rossetti’s work that he insisted upon

Rossetti giving him lessons; and then he wrote such a glowing account of

the Rossettis to his chum, William Morris, that Morris came up to see

for himself whether these things were true.

Morris met the Rossettis, spent the evening at their home, and went back

to Oxford filled with the idea of Utopia, and that the old world would

not find rest until it accepted the dictum of Mrs. Rossetti, “A few

plain things suffice.”

It was a woman who brought about the Epoch.

—–

The year Eighteen Hundred Fifty was certainly rich in gifts for Gabriel

Rossetti. He was twenty-two, gifted, handsome, intellectual, the adored

pet and pride of his mother and two sisters, and also the hero of the

little art group to which he belonged. I am not sure but that the lavish

love his friends had for him made him a bit smug and self-satisfied, for

we hear of Ruskin saying, “Thank God he is young,” which remark means

all that you can read into it.

At this time Rossetti had written many poems, and at least one great

one, “The Blessed Damozel.” He had also painted at least one great

picture, “The Girlhood of the Virgin,” a canvas he vainly tried to sell

for forty pounds, and which later was to be bought by the nation for the

tidy sum of eight hundred guineas, and now can not be bought for any

price–but which, nevertheless, may be seen by all, on the walls of the

National Gallery.

But four numbers of “The Germ” had been printed, and then the venture

had sunk into the realm of things that were, weighted with a debt of one

hundred twenty pounds. Of the fifty-one contributions to “The Germ”

twenty-six had been by the Rossettis. Dante Gabriel, always a bit

superstitious, felt sure that the gods were trying to turn him from

literature to art, but Christina felt no comfort in the failure.

Then came the championship of Ruskin, and this gave much courage to the

little group. Doubtless none knew they stood for so much until they had

themselves explained to themselves by Ruskin.

Then best of all came Burne-Jones and Morris, adding their faith to the

common fund and proving by cash purchases that their admiration was

genuine.

Rossetti’s poem, “The Blessed Damozel,” was without doubt inspired by

Edgar Allan Poe’s “Annabel Lee,” but with this difference, that while

Rossetti carried the sorrow clear to Paradise, Poe was content to leave

his sorrow on earth.

Being a painter of pictures as well as picturing things by means of

words, Rossetti had constantly in his mind some one who might pose for

the Damozel. She must be stately, sober, serious, tall, and possess “a

wondrous length of limb.” Her features must be strong, individual, and

she must have personality rather than beauty.

A pretty woman would, of course, never, never do. Where was such a model

woman to be found?

Christina wrote a beautiful sonnet about this Ideal Woman. Here it is:

One face looks out from all his canvases;

One selfsame figure sits or walks or leans:

We found her hidden just behind those screens,

That mirror gave back all her loveliness.

A queen in opal or in ruby dress,

A nameless girl in freshest Summer-greens,

A saint, an angel–every canvas means

The one same meaning, neither more nor less.

He feeds upon her face by day and night,

And she with true, kind eyes looks back on him,

Fair as the moon and joyful as the light:

Not wan with waiting, not with sorrow dim;

Not as she is, but was when hope shone bright;

Not as she is, but as she fills his dream.

Dante Gabriel was becoming moody, dreamy and melancholy; but not quite

so melancholy as he thought he was, since the divine joy was his of

expressing his melancholy in art. People submerged in melancholy are not

creative.

Rossetti was quite sure that Nature had never made as lovely a woman as

he could imagine, and his drawings almost proved it. But being a man he

never gave up the quest.

One day, Walter Deverell, one of the Brotherhood, came into Rossetti’s

studio and proceeded to stand on his head and then jump over the

furniture. After being reprimanded, and then interrogated as to reasons,

he told what he was dying to tell–that is, “I have found her!” Her name

was Elizabeth Eleanor Siddal, and she was an assistant to a milliner and

dressmaker in Oxford Street. She was seventeen years old, five feet

eight inches high, and weighed one hundred twenty pounds. Her hair was

of a marvelous, coppery, low tone, and her features were those of

Sappho. None of the assembled Brotherhood had ever seen Sappho, but they

had their ideas about her. Whether the dressmaker’s wonderful assistant

had intellect and soul did not trouble the young man. Dante Gabriel, the

Nestor of the group, twenty-two and wise, was not to be swept off his

feet by the young and impressible enthusiasm of Deverell, aged nineteen.

He sneezed and calmly continued his work at the easel, merely making

inward note of the location of the shop where the “find” was located.

Two hours later, Rossetti, perceiving himself alone, laid aside his

brushes and palette, put on his hat, and walked rapidly toward Oxford

Street. He located the shop, straggled past it, first on one side of the

street, then on the other, and finally boldly entered on a fictitious

errand.

Miss Siddal was there. He stared at her; she looked at him in

half-disdain. Suddenly his knees grew weak: he turned and fled.

Deverell boldly stalked the quarry the next day in company with his

mother, who was a customer of the shop. He failed to get an interview. A

little later, the mother went back alone, and put the matter before Miss

Siddal in a purely business light.

Elizabeth Eleanor was from a very poor family.

Her father was an auctioneer who had lost his voice, and she was glad to

increase the meager pay she was receiving by posing for the artists. She

was already a model, setting off bonnets and gowns, and her first idea

was that they wanted her for fashion-plates. Mrs. Deverell did not

disabuse her of this idea.

And so she posed for the class at Rossetti’s studio, duly gowned as

angels are supposed to be draped and dressed in Paradise.

Mrs. Deverell was present to give assurance, and all went well. The

young woman was dignified, proud, with a fine but untrained mind. As to

her knowledge of literature, she explained that she had read Tennyson’s

poems because she had found them on some sheets of paper that were

wrapped around a pat of butter she had bought to take home to her

mother.

Her general mood was one of silent good-nature, flavored with a dash of

pride, and an innocent curiosity to know how the picture was getting

along. It has been said that people who talk but little are quiet either

because they are too full for utterance, or because they have nothing to

utter. Miss Siddal was reserved, because she realized that she could

never talk as picturesquely as she could look. People who know their

limitations are in the line of evolution. The girl was eager and anxious

to learn, and Rossetti set about to educate her. In the operation he

found himself loving her with a mad devotion.

The other members of the Brotherhood respected this very frank devotion

and did not enter into competition with it, as they surely would have

done had it been merely admiration. They did not even make gentle fun

of it–it was too serious a matter with Rossetti: it was to him a

religion, and was to remain so to the day of his death. Within a week

after their meeting, “The House of Life” began to find form. He wrote to

her and for her, and always and forever she was his model. The color of

her hair got into his brush, and her features were enshrined in his

heart.

He called her “Guggums” or “Gug.” Occasionally, he showed impatience if

any one by even the lifting of an eyebrow seemed to doubt the divinity

of the Guggums.

There was no time for ardent wooing on his part, no vacillation nor

coyness on hers. He loved her with an absorbing passion–loved her for

her wonderful physical beauty, and what she may have lacked in mind he

was able to make good.

And she accepted his love as if it were her due, and as if it had always

been hers. She was not agitated under the burning impetus; no, she just

calmly and placidly accepted it as a matter of course.

It will hardly do to say that she was indifferent, but Burne-Jones was

led by Miss Siddal’s beautiful calm to say, “Love is never mutual–one

loves and the other consents to be loved.”

The family of Rossetti, his mother and sisters, must have known how much

of the ideal was in his passion. Mentally, Miss Siddal was not on their

plane; but the joy of Dante Gabriel was their joy, and so they never

opposed the inevitable. He, however, acknowledged Christina’s mental

superiority by somewhat imperiously demanding that Christina should

converse with Miss Siddal on “great themes.”

Ruskin has added his endorsement to Miss Siddal’s worth by calling her

“a glorious creature.”

Dante Gabriel’s own descriptions of Elizabeth Eleanor are too much

retouched to be accurate; but William Rossetti, who viewed her with a

critical eye, describes her as “tall, finely formed, with lofty neck;

regular, yet uncommon, features; greenish-blue, unsparkling eyes; large,

perfect eyelids; brilliant complexion, and a lavish wealth of dark

molten-gold hair.”

In the diary of Madox Brown for October Sixth, Eighteen Hundred

Fifty-four, is this: “Called on Dante Rossetti. Saw Miss Siddal, looking

thinner and more death-like, and more beautiful and more ragged than

ever; a real artist, a woman without parallel for many a long year.

Gabriel as usual diffuse and inconsequent in his work. Drawing wonderful

and lovely Guggums one after another, each one a fresh charm, each one

stamped with immortality, and his picture never advancing. However, he

is at the wall and I am to get him a white calf and a cart to paint

here; would he but study the Golden One a little more. Poor Gabriello!”

In Elizabeth Eleanor’s manner there was a morbid languor and dreaminess,

put on, some said, for her lover like a Greek gown, and surely

encouraged by him and pictured in his Dantesque creations.

Always and forever for him she was the Beata Beatrix. His days were

consumed in writing poems to her or painting her, and if they were

separated for a single day he wrote her a letter, and demanded that she

should write one in return, to which we once hear of her gently

demurring. She, however, took lessons in drawing, and often while posing

would work with her pencil and paper.

Ruskin was so pleased with her work that he offered to buy everything

she did, and finally a bargain was struck and he paid her one hundred

pounds a year and took everything she drew.

Possibly this does not so much prove the worth of her work as the

generosity of Ruskin. The dressmaker’s shop had been able to get along

without its lovely model, and art had been the gainer. At one time a

slight cloud appeared on the horizon: another “find” had been located.

Rossetti saw her at the theater, ascertained her name and called on her

the next day and asked for sittings. Her name was Miss Burden. She was

very much like Miss Siddal, only her face was pale and her hair wavy and

black. She was statuesque, picturesque, of good family, and had a

wondrous poise. Rossetti straightway sent for William Morris to come and

admire her. William Morris came, and married her in what Rossetti

resentfully called “an unbecoming and insufficiently short space of

time.”

For some months there was a marked coldness between Morris and

Rossetti, but if Miss Siddal was ever disturbed by the advent of Miss

Burden we do not know it. Whistler has said that it was Mrs. Morris who

gave immortality to the Preraphaelites by supplying them stained-glass

attitudes. She posed as Saint Michael, Gabriel, and Saint John the

Beloved, and did service for the types that required a little more

sturdiness than Miss Siddal could supply.

The Burne-Jones dream-women are very largely composite studies of Miss

Siddal and Mrs. Morris; as for Rossetti, he painted their portraits

before he saw them, and loved them on sight because they looked like his

Ideal.

—–

After Dante Gabriel and Elizabeth Eleanor had been engaged for more than

five years–that is, in the year Eighteen Hundred Fifty-five–Madox

Brown asked Rossetti this very obvious question: “Why do you not marry

her?” One reason was that Rossetti was afraid if he married her he would

lose her. He doted on her, fed on her, still wrote sonnets just for her,

and counted the hours when they parted until he could see her again.

Miss Siddal was not quite firm enough in moral and mental fiber to cut

out her own career. She deferred constantly to her lover, adopted his

likes and dislikes, and went partners with him even in his prejudices.

They dwelt in Bohemia, which is a good place to camp, but a very poor

place in which to settle down.

The precarious ways of Bohemia do not make for length of days. Miss

Siddal seemed to fall into a decline, her spirits lost their buoyancy,

she grew nervous when required to pose for several hours at a time.

Rossetti scraped together all his funds and sent her on a trip alone

through France. She fell sick there, and we hear of Rossetti working

like mad on a canvas, so as to sell the picture and send her money.

When she returned, a good deal of her old-time beauty seemed to have

vanished: the fine disdain, that noble touch of scorn, was gone–and

Rossetti wrote a sonnet declaring her more beautiful than ever. Ruskin

thought he saw the hectic flush of death upon her cheek.

Sorrow, love, ill-health, poverty, tamed her spirit, and Swinburne

telling of her, years after, speaks of “her matchless loveliness,

courage, endurance, humor and sweetness–too dear and sacred to be

profaned by any attempt at expression.”

Rossetti writing to Allingham says: “It seems to me when I look at her

working, or too ill to work, and think of how many without one tithe of

her genius or greatness of spirit have granted them abundant health and

opportunity to labor through the little they can or will do, while

perhaps her soul is never to bloom, nor her bright hair to fade; but

after hardly escaping from degradation and corruption, all she might

have been must sink again unprofitably in that dark house where she was

born. How truly she may say, ‘No man cared for my soul.’ I do not mean

to make myself an exception, for how long have I known her, and not

thought of this till so late–perhaps too late.”

In Rossetti’s love for this beautiful human lily there was something

very selfish, the selfishness of the artist who sacrifices everything

and everybody, even himself, to get the work done.

Rossetti’s love for Miss Siddal was sincere in its insincerity. The art

impulse was supreme in him and love was secondary. The nine years’

engagement, with the uncertain, vacillating, forgetful, absent-minded

habits of erratic genius to deal with, wore out the life of this

beautiful creature.

The mother-instinct in her had been denied: Nature had been set at

naught, and art enthroned. When the physician told Rossetti that the

lovely lily was to fade and die, he straightway abruptly married her,

swearing he would nurse her back to life. He then gave her the “home”

they had so long talked of; three little rooms, one all hung with her

own drawings and none other. He petted her, invited in the folks she

liked best, gave little entertainments, and both declared that never

were they so happy.

She suffered much from neuralgia, and the laudanum taken to relieve the

pain had grown into a necessity.

On the Tenth of February, Eighteen Hundred Sixty-two, she dined with her

husband and Mr. Swinburne at a nearby hotel. Rossetti then accompanied

her to their home, and leaving her there went alone to give his weekly

lecture at the Working Men’s College. When he returned in two hours, he

found her unconscious from an overdose of laudanum. She never regained

consciousness, breathing her last but a few short hours later.

—–

The grief of Rossetti on the death of his wife was pitiable. His friends

feared for his sanity, and had he not been closely watched it is quite

possible that one grave would have held the lovers. He reproached

himself for neglecting her. He cursed art and literature for having

seduced him away from her, and thus allowed her to grope her way alone.

He prophesied what she might have been had he only devoted himself to

her as a teacher, and by encouragement allowed her soul to bloom and

blossom. “I should have worked through her hand and brain,” he cried.

He gathered all the poems he had written to her, including “The House of

Life,” and tying them up with one of the ribbons she had worn, placed

the precious package by stealth in her coffin, close to the cold heart

that had forever stopped pulsing. And so the poems were buried with the

woman who had inspired them.

Was it vanity that prompted Rossetti after seven years to have the body

exhumed and recover the poems that they might be given to the world? I

do not think so, else all men who print the things they write are

inspired by vanity. Rossetti was simply unfortunate in being placed

before the public in a moment of spiritual undress. Everybody is

ridiculous and preposterous every day, only the public does not see it,

and therefore the acts are not ridiculous and preposterous. The conduct

of the lovers is always absurd to the onlooker, but the onlooker has no

business to look on–he is a false note in a beautiful symphony, and

should be eliminated.

Rossetti in the transport of his grief, filled with bitter regret, and

with a welling heart for one who had done so much for him, gave into her

keeping, as if she were just going on a journey, the finest of his

possessions. It was no sacrifice–the poems were hers.

At such a time do you think a man is revolving in his mind business

arrangements with Barabbas?

The years passed, and Rossetti again began to write–for God is good.

The grief that can express itself is well diluted; in fact, grief often

is a beneficent stimulus of the ganglionic cells. The sorrow that is

dumb before men, and which, if it ever cries aloud, seeks first the

sanctity of solitude, is the only sorrow to which Christ in pity turns

his eye or lends his ear.

The paroxysms of grief had given way to calm reflection. The river of

his love was just as deep, but the current was not so turbulent.

Expression came bringing balm and myrrh. And so on the advice of his

friends, endorsed by his own promptings, the grave was opened and the

package of poems recovered.

It was an act that does not bear the close scrutiny of the unknowing

mob. And I do not wonder at the fierce hate that sprang up in the breast

of Rossetti when a hounding penny-a-liner in London sought to picture

the stealthy, ghoul-like digging in a grave at midnight, and the

recovery of what he called “a literary bauble.” As if the man’s vanity

had gotten the better of his love, or as if he had changed his mind! Men

who know, know that Rossetti had not changed his mind–he had only

changed his mood.

The suggestion that gentlemen poets about to deposit poems in the

coffins of their lady-loves should have copies of the originals

carefully made before so doing, was scandalous. However, when this was

followed up with the idea that Rossetti should, after exhuming the

poems, have copies made and place these back in the coffin, and that the

performance of midnight digging was nothing less than petit larceny from

a dead woman, witnessed by the Blessed Damozel leaning over the bar of

Heaven–in all this we get an offense in literature and good taste which

in Kentucky or Arizona would surely have cost the penny-a-liner his

life.

If these poems had not been recovered, the world would have lost “The

House of Life,” a sonnet series second not even to the “Sonnets From the

Portuguese,” and the immortal sonnets of Shakespeare.

The way Rossetti kept the clothing and all the little nothings that had

once belonged to his wife revealed the depths of love–or the

foolishness of it, all depending upon your point of view. Mrs. Millais

tells of calling at Rossetti’s house in Cheyne Walk in Eighteen Hundred

Seventy, nearly ten years after the death of Elizabeth Eleanor, and

having occasion to hang her wraps in a wardrobe, perceived the dresses

that had once belonged to Mrs. Rossetti hanging there on the same hooks

with Rossetti’s raiment. Rossetti made apology for the seeming confusion

and said, “You see, if I did not find traces of her all over the house I

should surely die.”

A year after the death of his wife Rossetti painted the wonderful “Beata

Beatrix,” a portrait of Beatrice sitting in a balcony overlooking

Florence. The beautiful eyes filled with ache, dream and expectation are

closed as if in a transport of calm delight. An hourglass is at hand and

a dove is just dropping a poppy, the flower of sleep and death, into her

open hands. Of course the picture is a portrait of the dear, dead wife,

and so in all the pictures thereafter painted by Dante Gabriel for the

twenty years that he lived, you perceive that while he had various

models, in them all he traced resemblances to this first, last and only

passion of his life.

—–

In William Sharp’s fine little book, “A Record and a Study,” I find

this:

As to the personality of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, a great deal has

been written since his death, and it is now widely known that he was

a man who exercised an almost irresistible charm over those with

whom he was brought in contact. His manner could be peculiarly

winning, especially with those much younger than himself, and his

voice was alike notable for its sonorous beauty and for the magnetic

quality that made the ear alert when the speaker was engaged in

conversation, recitation or reading. I have heard him read, some of

them over and over again, all the poems in the “Ballads and

Sonnets,” and especially in such productions as “The Cloud Confines”

was his voice as stirring as a trumpet-note; but where he excelled

was in some of the pathetic portions of “The Vita Nuova” or the

terrible and sonorous passages of “L’Inferno,” when the music of the

Italian language found full expression indeed. His conversational

powers I am unable adequately to describe, for during the four or

five years of my intimacy with him he suffered too much to be a

brilliant talker, but again and again I have seen instances of that

marvelous gift that made him at one time a Sydney Smith in wit and a

Coleridge in eloquence.

In appearance he was, if anything, rather above middle height, and,

especially latterly, somewhat stout; his forehead was of splendid

proportions, recalling instantaneously the Stratford bust of

Shakespeare; and his gray-blue eyes were clear and piercing, and

characterized by that rapid, penetrative gaze so noticeable in

Emerson.

He seemed always to me an unmistakable Englishman, yet the Italian

element frequently was recognizable; as far as his own opinion was

concerned, he was wholly English. Possessing a thorough knowledge of

French and Italian, he was the fortunate appreciator of many great

works in their native tongue, and his sympathies in religion, as in

literature, were truly catholic. To meet him even once was to be the

better for it ever after; those who obtained his friendship can not

well say all it meant and means to them; but they know they are not

again in the least likely to meet with such another as Dante Gabriel

Rossetti.

In Walter Hamilton’s book, “AEsthetic England,” is this bit of most vivid

prose:

Naturally the sale of Rossetti’s effects attracted a large number of

persons to the gloomy, old-fashioned residence in Cheyne Walk,

Chelsea, and many of the articles sold went for prices very far in

excess of their intrinsic value, the total sum realized being over

three thousand pounds. But during the sale of the books, on that

fine July afternoon, in the dingy study hung round with the lovely

but melancholy faces of Proserpine and Pandora, despite the noise of

the throng and the witticisms of the auctioneer, a sad feeling of

desecration must have crept over many of those who were present at

the dispersion of the household goods and gods of that man who so

hated the vulgar crowd. Gazing through the open windows they could

see the tall trees waving their heads in a sorrowful sort of way in

the summer breeze, throwing their shifty shadows over the neglected

grass-grown paths, once the haunt of the stately peacocks, whose

medieval beauty had such a strange fascination for Rossetti, and

whose feathers are now the accepted favors of his apostles and

admirers. And so their gaze would wander back again to that

mysterious face upon the wall, that face as some say the grandest in

the world, a lovely one in truth, with its wistful, woeful,

passionate eyes, its sweet, sad mouth with the full red lips; a face

that seemed to say the sad old lines:

‘Tis better to have loved and lost,

Than never to have loved at all.

And then would come the monotonous cry of the auctioneer to disturb

the reverie, and call one back to the matter-of-fact world which

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, painter and poet, has left

forever–Going!–Going!–Gone!

——————————————

I made a few slap-dash notes while reading Little Journeys for the first time:

-I’ve always assumed that C. Rossetti’s poem In An Artist’s Studio is about Lizzie, and I still believe this, so I was a bit surprised that Hubbard wrote about it as if it was about a generic “Ideal Woman”.

-According to Hubbard’s account of Lizzie’s discovery, Gabriel made his way to the shop where Lizzie worked after Deverell told him of her–I love how Hubbard dramatizes this with Lizzie looking at Gabriel in “half-disdain” and Gabriel going weak in the knees.

-Hubbard states Lizzie’s father was an auctioneer who had lost his voice?

-But I loved this sentence. I don’t know why, it just made me chuckle. “They dwelt in Bohemia, which is a good place to camp, but a very poor place in which to settle down.”

-Hmm. States that Rossetti scraped together funds to send Lizzie to France when it was in fact Ruskin. But he is correct that Rossetti hurried to finish a picture while she was away in order to send her more money. The picture was Paolo and Francesca de Rimini.

-No mention of their stillborn child.

-I’d like to find the two books mentioned at the end: William Sharp’s A Record and a Study, and Walter Hamilton’s Aesthetic England.

Leave a Reply