Kirsty Stonell Walker is the author of Stunner, the Fall and Rise of Fanny Cornforth. (Available at Amazon.com

or Amazon.co.uk) Kirsty originally shared this post on her blog The Kissed Mouth and I am extremely grateful that she granted me permission to post it here as well.

——–

You will probably be aware by now that there will be a play on in London from the end of this month all about the tragic life of Elizabeth Siddal. The life of the ‘Pre-Raphaelite Supermodel’ has been shown on screen before, but this is apparently the first time she has appeared on stage. Maybe they have found a theatre with a door big enough to fit a bath through.

I wish them well and hope this will encourage more interest in Pre-Raphaelite art but it reminded me of an old niggle I have. Elizabeth Siddal’s name is synonymous with two things: baths and tragedy. Is it fair or are we participating in her tragedy by reducing her to this?

You know me, I loathe assumption. Most of the ten years it took me to write Stunner was spent saying ‘No, she wasn’t a cockney,’ and ‘No, she wasn’t an illiterate prostitute! She could read!’ However, when you are reading about someone for the first time you have to wade through the conclusions of others before you can afford to make your own. For example, think about a short summary of Siddal’s life. It’s bound to involve a bath-tub and an early death, these are unavoidable points in her life. Possibly your summary involves painting, poetry, possibly infidelity and sadness. Does it involve her laughing and chasing around the Red House? Does it involve being sponsored by the leading art critic of the day? Does it involve her finding out her artworks will appear in America? How many of those later points appear in the ‘fictional’ depictions of her?

So, we have poor Gug, as Rossetti called her, packing quite a bit into her 32 years. She loved poetry, after apparently discovering a poem by Tennyson wrapped around a pat of butter as a child. See, less young ‘uns these days would long to go on X-Factor if we printed poems on butter wrappers. They would all want to be Pam Ayres, and rightly so. She longed to paint, possibly a by-product of being thrust into the art world by her stint of modelling. Her engagements before Ophelia seem inconsequential, even though they were for Deverell, who discovered her. Ophelia is the moment she begins to exist for us as an icon.

I have just been reading about the many and varied theories about what followed. Standard story is that the candles went out, she got cold, got ill and that affected her for the rest of her life. Add to this that she may have already been taking laudanum, she may have been anorexic, she may have been a hypochondriac, she may have been taking other preparations that were slowly poisoning her, her parents may have been on the make. Goodness, how complicated. I wonder if the whole palaver around her near-drowning makes Ophelia remain such a prominent image of the age. Certainly the popularity of the painting seems to have sealed Siddal’s fate to be ever the dying dame, much in the same way as certain actors can never be seen as other than their most popular role. It is much to Millais’ credit that it is almost impossible to imagine the fictional character of Ophelia as being anything other than the perishing Elizabeth Siddal.

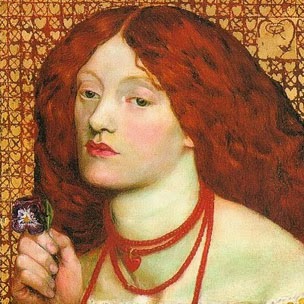

Why do we not think of her like this, at an easel? She painted for around a decade and wrote for possibly longer. Her poems explored melancholic themes but her art works were as varied as others in her circle. In his drawings of her at work, Rossetti shows a woman who is busy and well. I do not look at the above image and think ‘Poor Lizzie’ because there is no need. I pity her no more than any other woman artist of the age, and she achieved a great deal.

Something I have talked about before is the shortening of names. I know I have discussed this with people in various contexts but I am always intrigued by the way that we shorten or change the names of famous people, notably women. Elizabeth Rossetti becomes Lizzie Siddal but does this tell us anything else? People shorten the names of others for many reasons; a sense of familiarity with a person, a sense of possession, an empathy or identification. Undoubtedly Elizabeth was known as ‘Lizzie’ by her friends but is that a good enough reason for us to call her that? I am variously known as ‘Kiz’, ‘Moo’, ‘Nelly’ and far worse, but none of those should be used by my future and no doubt plentiful biographers. Why not use my full name under which I work? I would think it a terrible presumption if someone I did not know referred to me as ‘Kirst’ (lawks, it sounds like ‘cursed’). By shortening a name you are assuming the role of acquaintance of the person, but also it stops the person being at a distance, up on a pedestal, which they might be if you admired them. It’s hard to think of Alfred Lord Tennyson as being ‘Alfie’ or ‘Fred’ but presumably he must have had a nickname. A nickname humanizes a subject, but is that helpful? I would add that it seems common in newspapers to shorten names of victims to involve the reader with their plight, for sad example would you think of Madeleine McCann or Maddie?

Now, there is nothing wrong with seeing a person in the past as a human being, if fact I would like more such understanding shown to Rossetti who seemingly is either held on a pedestal or seen as a devil devoid of feeling. However, a byproduct of seeing a person as ‘human’ is that naturally we see their all-too-human foibles and failings. It was alright for me; writing about Fanny could only reveal better things than were already said about her, but when the woman is revered then the revelations can only be detrimental in order to be ‘revelations’. Also it seems to me that we don’t like uncertainty, we don’t like the unexplained in life stories. Therefore, more often than not Elizabeth Siddal ‘killed herself’ rather than ‘took an accidental overdose’ because it has a definite point rather than raise more questions.

far more interesting than saying he used existing sketches

So where is all my rambling leading? Well, firstly to make a general point: Sometimes I fear that biography of successful women reinforces prejudice in a perverse way. Speaking as a biographer, it’s a hard balancing act, showing a woman in all her glory without backing up the views of the society they lived in because they lived in that society and were subject to it. Elizabeth undoubtedly found life as an artist far more difficult than her erstwhile lover because any woman attempting to achieve success in such an elitist world is bound to find it difficult. Goodness, there are scores of men who found it damn near impossible too, but we don’t find them so pitiful as poor, tragic Lizzie. Not even Walter Deverell gets labelled as ‘tragic’ as often as Mrs Rossetti. It somehow seems a little improper to bring up the private life of men, or to lend it equal weight, when writing biography as if we are trying to excuse them or lessen their impact. Many men of Elizabeth’s circle could be labelled as tragic – look at Swinburne! Maybe we linger on women’s private lives because they played such a huge part in their lives, their ‘proper sphere’ was the domestic, the private, and so obviously that would have a massive impact in who they were and what they did. It held women back, it filled their time, it even killed a few of them (in childbirth), it was seen by society as being their ‘job’ so any attempts on their part to participate in a ‘male’ occupation has to be seen in the context of what they weren’t doing or trying to balance.

So why is Lizzie special? A combination of things seem to affect Miss Siddal. Firstly, she’s a woman, therefore biography tells us about her private life. We know she was led a merry dance by Rossetti, but then Georgiana Burne-Jones had a hard marriage and Jane Morris’ was troubled. There has to be more to the relationship than unending misery, and there are tales of laughter and joy. She didn’t almost die during every modelling assignment, but then possibly none of the other pictures were as astonishing as Ophelia. Mind you, we don’t assume Millais had a tragic life because he created the image. It is a brilliant image of death but all the credit, emphasis, and blame is placed on the model. That’s ridiculous. That’s like saying the tiny robin in the corner had a tragic life because he appeared in Ophelia. Yes, she had an accident while modelling but I wonder if she had been posing for a more positive subject when she had the accident, would we see her in a different light?

I don’t think it helps that a great deal of Pre-Raphaelite-ness is the melancholic, the tragic, the doomed, the sinister. As a person in a movement, of course Elizabeth would look the part. I love the photo of her in her ‘melancholic swoon’ but I don’t think she was like that any more than any of the various pictures of me give you a full idea of what I am like as a person. I would be very interested to find out what someone who has met me after following the blog thought I would be like. Lawks, can you imagine…?

Anyway, back to Lizzie. For some reason we are stuck with the epithet ‘tragic’ when describing her life but that lessens her because it makes her appear helpless. The majority of her life was not tinged with tragedy, in fact proportionately more of her life was spent in victory than in sorrow. She spent one afternoon in a bath tub but this dominates our vision of her. I wonder if the tragedy of Elizabeth Siddal is that we can’t let her be happy.

Lizzie Siddal is at the Arcola Theatre, London E8, from 20 November – 21 December 2013.

Lizzie Siddal is at the Arcola Theatre, London E8, from 20 November – 21 December 2013.

Leave a Reply