The text below is transcribed from Volume I of The Life and Letters of Sir John Everett Millais:

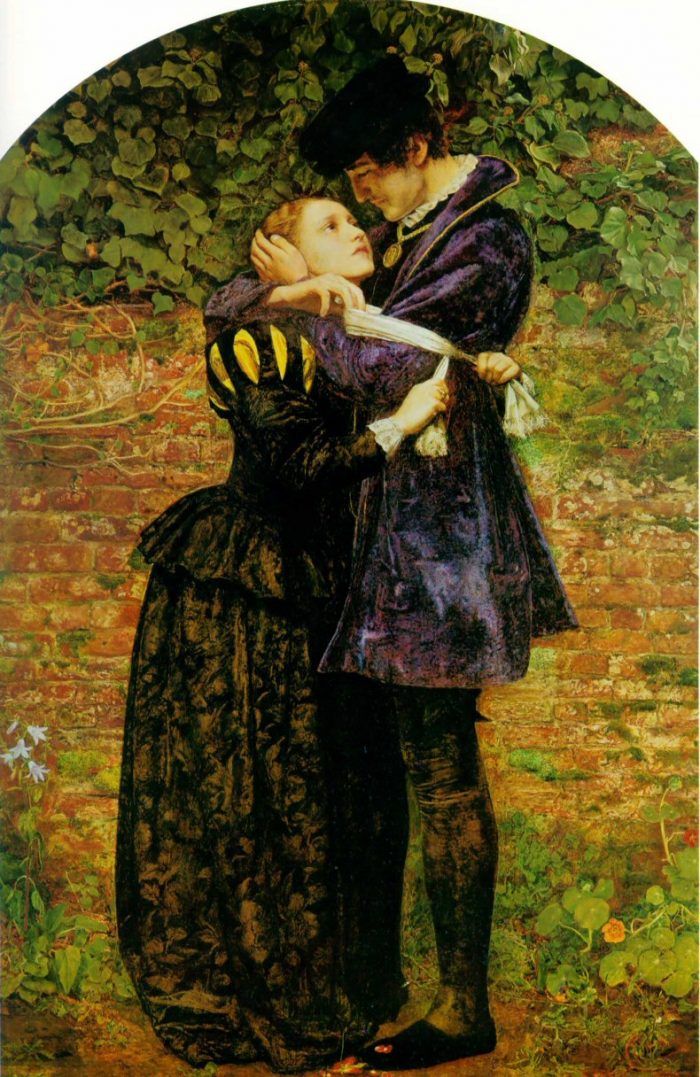

“Ophelia” and “The Huguenot”, both of which Millais painted during the autumn and winter of 1851, are so familiar in every English home that I need not attempt to describe them here. The tragic end of “Hamlet’s” unhappy love had long been in his mind as a subject he should like to paint; and now while the idea was strong upon him he determined to illustrate on canvas the lines in which she is presented as floating down the stream singing her last song:

There on the pendant boughs her coronet weeds

Clamb’ring to hang, an envious sliver broke,

When down her weedy trophies and herself

Fell in the weeping brook. Her clothes spread wide

And, mermaid-like, awhile they bore her up;

Which time she chaunted snatches of old tunes,

As one incapable of her own distress,

Or like a creature native and indued

Unto that element; but long it could not be

Till that her garments, heavy with their drink,

Pull’d the poor wretch from her melodious lay

To muddy death.

Near Kingston, and close to the home of his friends the Lempriéres, is a sweet little river called the Ewell, which flows into the Thames. Here, under some willows by the side of a hayfield, the artist found a spot that was in every way suitable for the background of his picture, in the month of July, when the river flowers and water-weeds were in full bloom. Having selected his site, the next thing was to obtain lodgings within easy distance, and these he secured in a cottage next to Kingston, with his friend Holman Hunt as a companion. They were not there very long, however, for presently came into the neighbourhood two other members of the Pre-Raphaelite fraternity, bent on working together; and uniting with them, the two moved into Worcester Park Farm, where an old garden wall happily served as a background for the “Huguenot,” at which Millais could now work alternately with the “Ophelia”.

It was a jolly bachelor party that now assembled in the farmhouse–Holman Hunt, Charlie Collins, William and John Millais–all determined to work in earnest; Holman Hunt on his famous “Light of the World” and “The Hireling Shepherd,” Charlie Collins at a background, William Millais on water-colour landscapes, and my father on the backgrounds for the two pictures he had then in hand.

From ten in the morning till dark the artists saw little of each other, but when the evenings “brought all things home” they assembled to talk deeply on Art, drink strong tea, and discuss and criticise each other’s pictures.

Fortunately a record of these interesting days is preserved to us in Millais’ letters to Mr. and Mrs. Combe, and his diary–the only one he ever kept–which was written at this time, and retained by my uncle William, who has kindly placed it at my disposal. Here are some of his letters–the first of which I would commend to the attention of Max Nordau, referring as it does to Ruskin, whom Millais met for the first time in the summer of this year. It was written from the cottage near Kingston before Millais and Hunt removed to Worcester Park Farm.

To Mrs. Combe

“Surbiton Hill, Kingston,

“July 2nd, 1851

“My Dear Mrs. Combe, – I have dined and taken breakfast with Ruskin, and we are such good friends that he wishes me to accompany him to Switzerland this summer…We are as yet singularly at variance in our opinions upon Art. One of our differences is about Turner. He believes that I shall be converted on further acquaintance with his works, and I that he will gradually slacken in his admiration.

“You will see that I am writing this from Kingston, where I am stopping, it being near to a river that I am painting for ‘Ophelia’. We get up (Hunt is with me) at six in the morning, and we are at work by eight, returning home at seven in the evening. The lodgings we have are somewhat better than Misstress King’s at Botley, but are, of course, horribly uncomfortable. We have had for dinner chops and suite of peas, potatoes, and gooseberry tart four days running. We spoke not about it, believing in the certainty of some change taking place; but in private we protest against the adage that ‘you can never have too much of a good thing.’ The countryfolk here are a shade more civil than those of Oxfordshire, but similarly given to that wondering stare, as though we were as strange a sight as the hippopotamus.*

“My martyrdom is more trying than any I have hitherto experienced. The flies of Surrey are more muscular, and have a still greater propensity for probing human flesh. Our first difficulty was…to acquire rooms. Those we now have are nearly four miles from Hunt’s spot and two from mine, so we arrive jaded and slightly above that temperature necessary to make a cool commencement. I sit tailor-fashion under an umbrella throwing a shadow scarcely larger than a halfpenny for eleven hours, with a child’s mug within reach to satisfy my thirst from the running stream beside me. I am threatened with a notice to appear before a magistrate for trespassing in a field after the said hay be cut; am also in danger of being blown by the wind into the water, and becoming intimate with the feelings of Ophelia when that lady sank to muddy death, together with the (less likely) total disappearance, through the voracity of the flies. There are two swans who not a little add to my misery by persisting in watching me from the exact spot I wish to paint, occasionally destroying every water-weed within their reach. My sudden perilous evolutions on the extreme bank, to persuade them to evacuate their position, have the effect of entirely deranging my temper, my picture, brushes, and palette; but, on the other hand, they cause those birds to look most benignly upon me with an expression that seems to advocate greater patience. Certainly the painting of a picture under such circumstances would be a greater punishment to a murderer than hanging.

I have read the Sheepfolds, but cannot give an opinion upon it yet. I feel it very lonely here. Please write before my next.

My love to the Early Christian and remembrances to friends.

Very affectionately yours,

John Everett Millais

*It was in this year, 1850, that the first specimen of the hippopotamus was seen in London. Millais seems to have been of the same opinion as Lord Macaulay, who says: “I have seen the hippopotamus, both asleep and awake; and I can assure you that, awake or asleep, he is the ugliest of the works of God.”